Jetrin Chusacultanachai

“ฉบับนี้น้องเจ็ตจะเจาะลึกลงไปถึงรายละเอียดเชิงวิศวกรรมของระบบขับเคลื่อนจรวดด้วยไอออน เชิญติดตามอ่านกันต่อได้เลย”

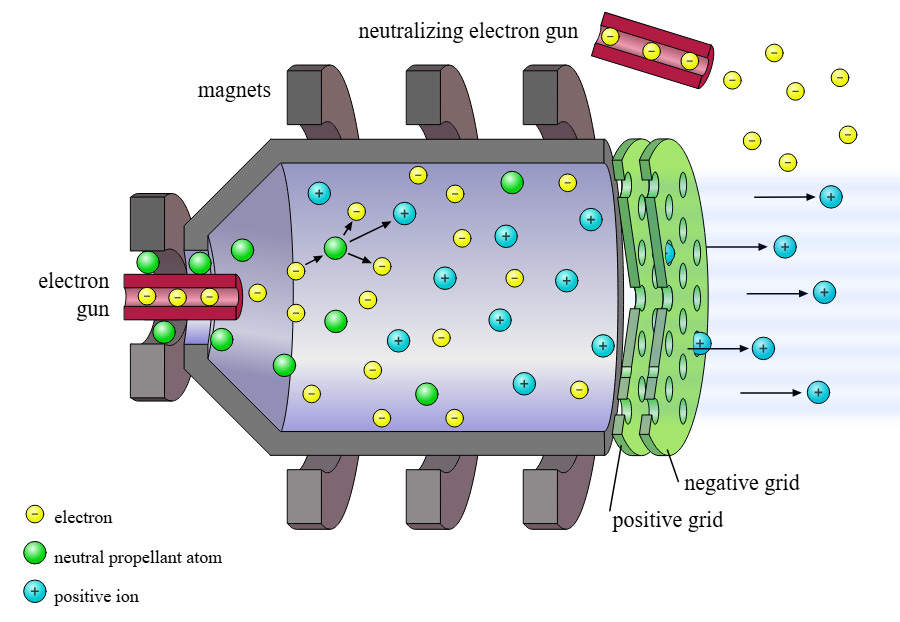

Gridded ion thrusters were the first to be designed and built. They take a propellant, commonly xenon, but others do exist, and shoot electrons at propellant atoms. These collisions with the electrons knock off one of the propellant atom’s own valence electrons, ionizing it. To create a potential difference which will accelerate the ions, we can place a sheet of metal at the exhaust end of the thruster in order to accelerate them to high speed.

We then cut holes in it to allow the ions to go through the holes and propel the spacecraft forward. This is called the accelerator grid, and is the basis of our thruster.

However, there is a problem; there is nothing stopping these fast moving positive ions from hitting the accelerator grid, wearing it down and eventually breaking the thruster. To solve this, we put a positively charged grid in front of the accelerator grid, which is called the screen grid. As positive charges repel each other, the ions will be repelled enough so they do not hit either grid, but not so much that they are repelled from the accelerator grid itself, causing most of the ions to go through the holes and generate thrust.

Finally, we collect the electrons left behind by the now ionized particles with magnets and we shoot them out with the ions to neutralize the spacecraft. Without this, the spacecraft would eventually develop a strong enough negative charge to pull back the positively charged ions, essentially making the propulsion system useless.

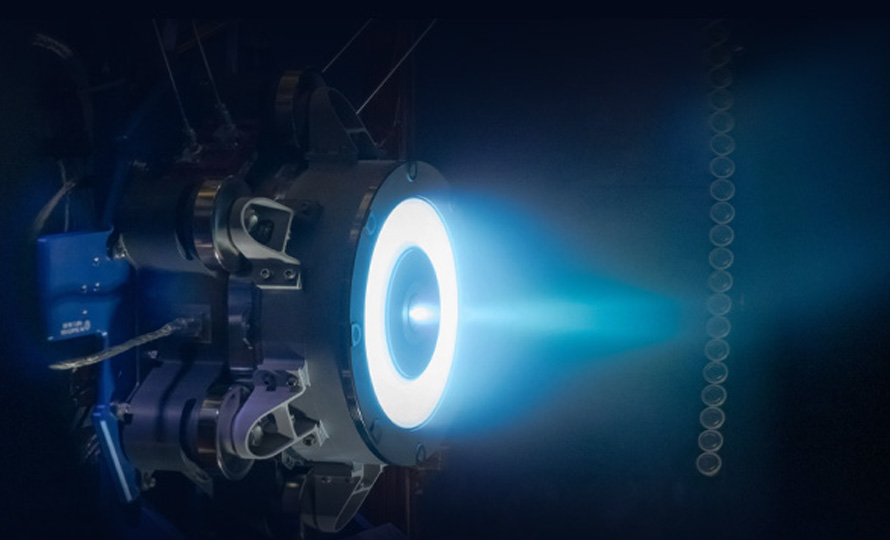

This is the original and most basic form of the gridded ion thruster. Pictured below is a diagram of such a thruster.

A diagram of a gridded ion thruster.

Source: Oona Räisänen, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The original two-grid design has since been improved by adding additional grids in order to further increase efficiency and durability. A 3-grid design adds an extra, neutrally charged grid after the accelerator grid to prevent the ions which have not been neutralized from coming back and hitting the accelerator grid at full speed, increasing the maximum safe potential difference, and therefore the maximum specific impulse. Modern 3-grid ion thrusters can hit around 4000 s of specific impulse[1].

In 2012, the ESA also tested a 4-grid design, with an extra set of screen and accelerator grids to extract the ions from the ionization chamber in order to further increase the maximum potential difference. This 4-grid hit specific impulses of up to 19,200 s, still the most efficient ever built (excluding solar sails and other methods which inherently rely on outside forces).

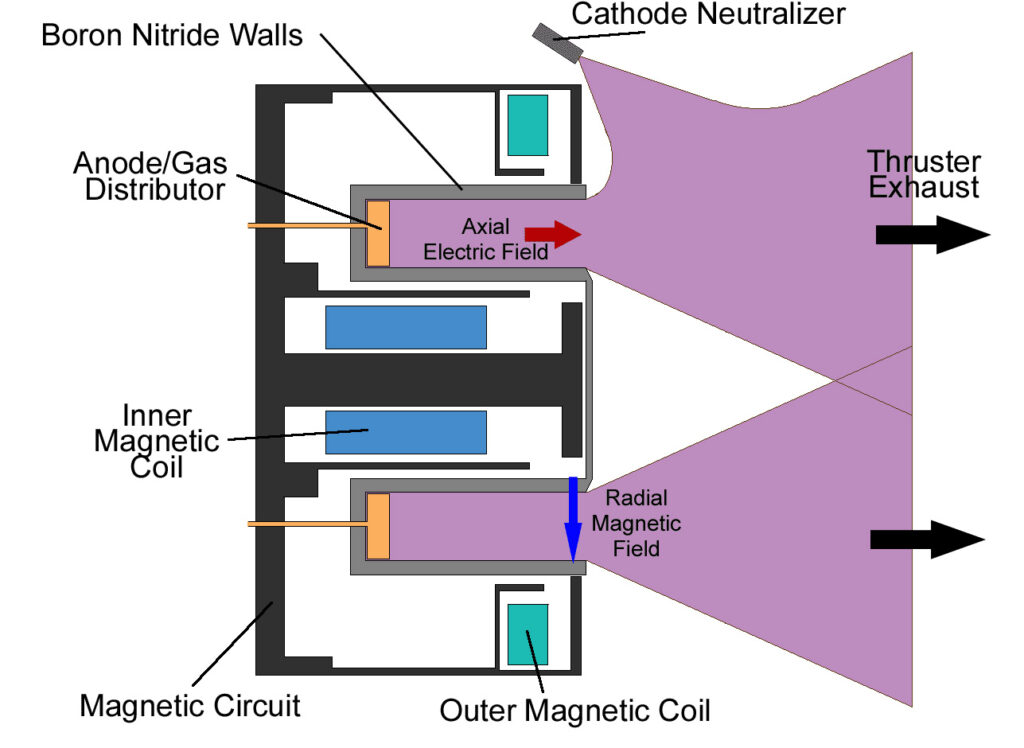

On the other hand, Hall effect thrusters do not use physical grids at all. Rather they use “virtual grids”, which are electrons trapped by a magnetic field.

In this thruster, we have a cathode (place of negative charge) placed near the thruster exhaust and pointing outwards, and an anode (place of positive charge) placed inside of the thruster. To begin, we apply a voltage across this circuit, creating an electric field which points spaceward. This also pushes electrons out of the cathode, which attempt to move towards the anode, like in any other circuit.

However, in between the cathode and the anode, we have placed electromagnets, which create a magnetic field, trapping the electrons in their middle of their journey. This crossing of a magnetic and electric field also leads to the Lorentz force pushing the electrons around in a circle around the electromagnet, causing the electrons to spin around the thruster really fast, upwards of 400 km/s. This flow of electrons is called the Hall current, and is also where the thruster gets its name. As these electrons are prevented from reaching the anode, this magnetic field acts like a resistor would in a circuit.

As a result, a potential difference builds up between the cathode and anode (negative potential near the cathode, positive potential near the anode), which will be our main method of ion acceleration.

While all of this is happening, Xenon (or some other propellant gas) is being injected into the chamber, and is slowly moving spaceward due to diffusion. When they eventually reach the magnetic field, some of them will collide with an electron, and some of these collisions are energetic enough to knock an electron off the propellant atom, creating a positively charged ion.

This ion is then launched out into space due to the aforementioned buildup of negative potential near the exhaust, and it takes an electron from the cathode with it to keep the whole system neutral. The electrons in the field, after colliding with hundreds of different propellant atoms, eventually lose their momentum, and drift closer, and closer to the anode, eventually entering it and finally completing the circuit.

However, even after accounting for all types of collisions, there are still more electrons reaching the anode than there should be. This “anomalous transport” is why Hall thrusters currently cannot be simulated accurately.

A diagram of a Hall effect thruster.

Source: David Staack (Keenan Pepper at en.wikipedia), Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hall thrusters typically have specific impulses between 1200-2500 s, although some designs have been tested with up to 8000 s. While they have lower specific impulses compared to gridded ion thrusters, Hall thrusters actually work better than gridded ion thrusters for many applications because they are generally much smaller and lighter than a gridded ion thruster, while simultaneously lasting longer due to them not having physical grids for ions to run into. They also typically provide more thrust for the same power as gridded ion thrusters.

While the most efficient thruster ever produced was a gridded ion thruster, the electric thruster with the most thrust ever produced was the University of Michigan’s X3 Hall thruster, which used multiple nested accelerator channels to achieve 5.4 newtons of thrust. This force is comparable to a water bottle resting in your hand instead of a sheet of paper.

Currently, most satellites in LEO usually use Hall thrusters. This is because such satellites don’t actually need to move that much (usually they just have to tweak their orbits after launch, stay in formation, and de-orbit themselves, if even that), so efficiency isn’t actually that important beyond a certain point; The mass of fuel is already quite small, and the mass of all that extra power infrastructure is comparatively quite heavy.

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites use Hall thrusters for exactly this reason.

SpaceX’s Starlink satellites.

Source: SpaceX, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

However, this difference in efficiency between the two thruster types becomes far more significant when we are faced with longer missions, as the extra fuel needed to accelerate the spacecraft an acceptable amount is now a significant enough portion of the spacecraft’s total mass such that an increase in efficiency will correspond to a significant weight saving. This is why gridded ion thrusters are favored by missions which venture into deep space, like NASA’s Dawn mission which was sent to the asteroid belt to investigate the protoplanets Ceres and Vesta. This mission required a change in velocity of over 11 km/s, much more than any LEO satellite would ever need.

In recent years, much discussion around space has centered on bringing humans to Mars, and ion thrusters have been proposed many times as a possible way to bring enough cargo to establish a habitable base for humans on Mars. While there are currently concerns around transfer time, and other practical factors, their potential cannot be denied. The required change in velocity to get from low earth orbit to mars is approximately 9 km/s under ideal conditions. To move a 10-ton base from earth to Mars, the NASA NEXT-C would require about 2500 kg of fuel, while the Atlas V’s second stage (which launched the perseverance rover to Mars) would require about 66,800 kg, not to mention the weight savings in the first stage. A fuel saving this significant has the potential to be game-changing when it comes to costs of turning humanity into an interplanetary civilization.

For this reason, electric propulsion may very well be the engines which propel us into the future, one ion at a time.

ประวัติผู้เขียน

Jetrin (Jet) Chusacultanachai is a sophomore (มัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4) at the Hotchkiss school in Lakeville, Connecticut. Jet has had a love for Engineering at a young age. In middle school, Jet competed and received awards at multiple international robotics competitions, and is now part of Hotchkiss’s FTC team. Jet has also founded a rocketry team to compete in the American Rocketry Challenge, and other related competitions. Additionally, he is currently researching the feasibility of a CubeSat which can transfer from LEO to GEO using such thrusters. Jet takes joy from sharing his love for Engineering with others. He teaches kids basic python, and helped run a rocketry workshop for children with the robotics team last year. He aims to expand his knowledge sharing on science/space to inspire a larger audience by writing this article and more. After High school, Jet plans to pursue Aerospace Engineering as a career.