Jetrin Chusacultanachai

“น้องเจ็ตเป็นเด็กมัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4 ที่สนใจเรื่องการสื่อสารวิทยาศาสตร์ผ่านการเขียนบทความ (ดูประวัติเพิ่มเติมท้ายบทความ) และนี่คือบทความเกี่ยวกับระบบขับเคลื่อนจรวดด้วยไอออนที่น่าสนใจ เนื่องจากเพื่อให้ความยาวเหมาะสมกับนิตยสารสาระวิทย์ จึงขอแบ่งเนื้อหาออกเป็น 2 ตอนย่อย โดยในตอนแรกจะกล่าวเน้นถึง “หลักการทำงานพื้นฐาน” ของระบบขับเคลื่อนจรวดแบบมาตรฐานที่ใช้การเผาไหม้เชื้อเพลิงเคมีสร้างแรงขับดันและการใช้ไอออนสร้างแรงขับดัน และในตอนที่สองจะกล่าวเจาะลึกลงไปถึงรายละเอียดเชิงวิศวกรรมของระบบขับเคลื่อนจรวดด้วยไอออน”

From the Chinese gunpowder rockets of the 10th century, to the Saturn V rocket, to SpaceX’s current Raptor engine, rockets have typically been powered chemically, i.e. sticking a bunch of stuff in a tube and blowing it up. This has been the best method for most rockets throughout most of history, because we need to get a lot of stuff from the ground into the sky or space.

An early Chinese gunpowder rocket.

Source: NASA, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

As stuff is heavy, and gravity is a thing, we need an equally strong force to fight against it, hence the relatively simple, and high thrust chemical rockets. However, once you get into space, more specifically orbit, our inertia can fight gravity for us, giving us the freedom to use propulsion systems with less thrust, but more efficiency, greatly reducing cost.

But how do we define efficiency?

When it comes to rocket propulsion, specific impulse is usually used. Specific impulse is defined as total impulse divided by the mass of fuel expended ![]() [1], i.e. how much use you can get per kilogram of fuel, taking units of meters per second. Curiously, this has the same units as velocity, and as all the values are from the engine’s exhaust, we can guess that specific impulse is actually the engine’s exhaust velocity, and this guess would be right.

[1], i.e. how much use you can get per kilogram of fuel, taking units of meters per second. Curiously, this has the same units as velocity, and as all the values are from the engine’s exhaust, we can guess that specific impulse is actually the engine’s exhaust velocity, and this guess would be right.

Therefore, we can increase our specific impulse by increasing our exhaust velocity.

However, specific impulse is usually measured in seconds for simplicity, which we get by replacing mass on the bottom with weight, and then dividing by standard gravity at sea level. This leads to a very nice intuition that an engine with 1 second of specific impulse burning 1 kilogram of fuel will produce 1 kilogram of force (i.e. levitate) for 1 second (assuming this engine has no mass).

Now we know what specific impulse is, we can discover why it is so important. Rockets are all about bringing stuff into space. The more mass this stuff has, the more fuel you need. Unfortunately for us, fuel also has mass, which needs to be propelled by more fuel, which has more mass, etc. Also if we need to move our stuff while we’re in space, we will need more fuel to move it, meaning even more fuel to get that into orbit.

This recursive cycle of fuel needing to be supported by more fuel leads to rockets having their mass taken up by fuel.

The Saturn V rocket.

For example, the Saturn V’s first stage’s mass was over 94% fuel[2], not even accounting for all the tanks needed to store it, which also increase in mass as the mass of fuel increases.

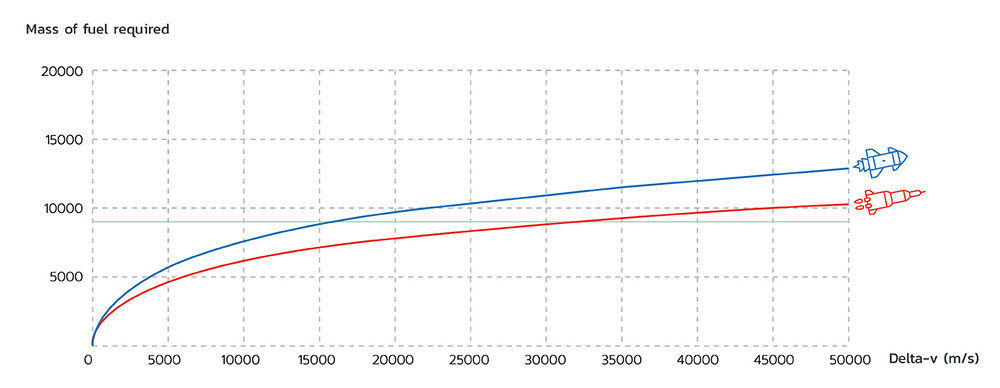

To examine this more mathematically, we use the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation ![]() [3] which governs the change in velocity that can be gained by a rocket with a certain specific impulse burning a certain amount of fuel under ideal conditions (no air resistance, no gravity, cows are spheres, etc.). From this equation, we can see that change in velocity scales linearly with specific impulse, but somewhat logarithmically with change in mass, and by plotting some values, the full extent of this can be known.

[3] which governs the change in velocity that can be gained by a rocket with a certain specific impulse burning a certain amount of fuel under ideal conditions (no air resistance, no gravity, cows are spheres, etc.). From this equation, we can see that change in velocity scales linearly with specific impulse, but somewhat logarithmically with change in mass, and by plotting some values, the full extent of this can be known.

To reach low earth orbit from the ground (~9 km/s needed), it would take the Saturn V about double the fuel that it would take the SpaceX raptor engine, even with such a seemingly marginal difference in specific impulse (263 s vs 327 s), and this gap would only grow as the required change in velocity also grows.

Now we know why we need it, we can now turn to achieving a higher specific impulse. As we know, a faster exhaust velocity results in higher specific impulse. So now we need to know how we can accelerate the ions to a high speed. If we first ionize the propellant atoms by knocking electrons off of it, and then place something with negative voltage in a direction, there is a difference in potential between the highly positive potential of the ions and the negative potential of this object, the ions will move, as charged particles move when there is a difference in electric potential (a voltage).

The Raptor Engine:

A testament to the power of chemical propulsion.

Source: SpaceX, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The more negative the potential of the attractor, the faster the ions will be accelerated. This is the principle which makes electric propulsion work, and it can be scaled up to be many times more efficient than a chemical rocket.

Specific impulse vs mass of fuel required to enter LEO, Plotted in Desmos. Blue is SpaceX Raptor first stage (327 s), Red is NASA Saturn V first stage (263 s). Both Isp values are for sea level. Graphs use a dry mass of 1000 kg, so they fit within a reasonable aspect ratio, although this doesn’t impact the ratio between them. If you want to try this out for yourself, remember to multiply by gravity. Y axis: Mass of fuel required, X axis:

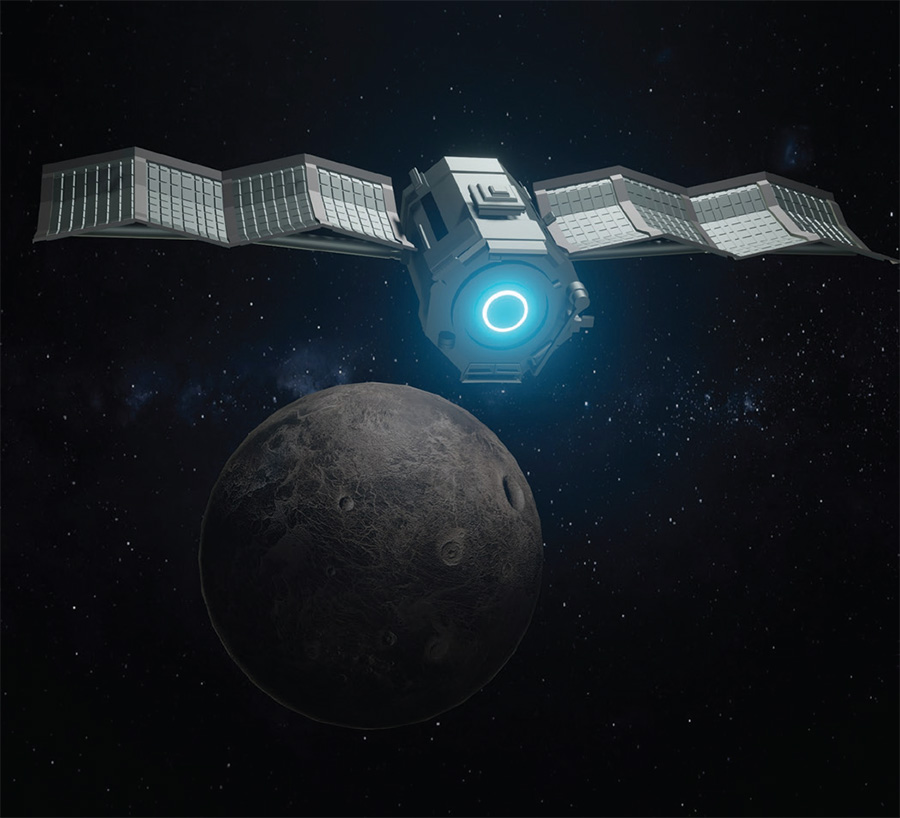

However, electric propulsion systems also have their own constraints. Firstly, they have an extremely low thrust when compared to their chemical counterparts, in the range of tens of millinewtons for even the largest thrusters, comparable to a sheet of A4 paper at rest in the palm of your hand. They also require large amounts of electrical power, and this requirement grows the more efficient the thruster is. As specific impulse is proportional to exhaust velocity, and kinetic energy is proportional to the square of velocity, the minimum amount of electrical energy required to run the engine scales quadratically with specific impulse. Therefore if we need to double the specific impulse of our engine, we would need to just about quadruple the amount of electrical power if we wanted the thrust to remain the same.

While the sun can provide a limitless supply of electrical energy to our satellite, the maximum solar power able to be extracted in low earth orbit per square meter (or solar flux) is only about 1.4 kilowatts. The best solar panels can only currently operate at around 30-40% efficiency, further limiting our power to around 560 watts per square meter of solar panel area. Due to this, the mass of the solar panels required to operate such a thruster may very well outweigh the fuel saved by the thruster itself. Furthermore, the added weight and added complexity of a high specific impulse thruster may also cancel out any fuel savings.

With this information, we can finally examine the two most popular electric thruster designs: the Gridded ion thruster, and the Hall effect thruster. [To be continued]

[1] The top part can also be written as change in momentum, and the whole equation can be rewritten many different ways.

[2] https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/static/history/afj/ap10fj/pdf/19700015780_as-505-a10-saturn-v-technical-info-summary.pdf p.35

[3] Change in velocity = specific impulse (in seconds) * standard gravity at sea level * the natural log of (mass before burn / mass after burn)

เกี่ยวกับผู้เขียน

Jetrin (Jet) Chusacultanachai is a sophomore (มัธยมศึกษาปีที่ 4) at the Hotchkiss school in Lakeville, Connecticut. Jet has had a love for Engineering at a young age. In middle school, Jet competed and received awards at multiple international robotics competitions, and is now part of Hotchkiss’s FTC team. Jet has also founded a rocketry team to compete in the American Rocketry Challenge, and other related competitions. Additionally, he is currently researching the feasibility of a CubeSat which can transfer from LEO to GEO using such thrusters. Jet takes joy from sharing his love for Engineering with others. He teaches kids basic Python, and helped run a rocketry workshop for children with the robotics team last year. He aims to expand his knowledge sharing on science/space to inspire a larger audience by writing this article and more. After High school, Jet plans to pursue Aerospace Engineering as a career.